Most of the available published research on serendipity relates to serendipitous occurrences within the domains of applied research, scientific discovery, invention, and technological development. There is also a fair amount of research on serendipity in the field of information science, particularly as it affects information seeking and discovery.

There is considerably less research on the prospect of stimulating serendipity for personal, professional, or entrepreneurial gain. However, the impact of serendipity in business is increasingly acknowledged, and there are many books and articles that address the topic.

To distinguish opportunity-driven or entrepreneurial serendipity stimulation from serendipitous invention or discovery, I will sometimes use the term gainful serendipity.

Gainful serendipity is more than just a “eureka” or “a-ha” moment. Before we have that sort of epiphany, we must prepare ourselves, and after it, work must be done before we realize a benefit.

Without the application of insight gained through preparation, we might fail to experience the eureka moment altogether. And without focused effort, we will almost certainly fail to reap any reward even if we do have such an experience.

A lot of researchers attempt to define, categorize, classify, or measure serendipity in various ways. But we don’t necessarily need to measure or quantify serendipity, we only need to acknowledge that it exists, that we can prepare for it, and that it can be stimulated.

Gainful serendipity is a process, from preparation to benefit realization. Having a model or framework to guide us through the process keeps us from fruitlessly scattering our energy and effort.

By modeling a process, we have a visual representation that helps us more deeply understand it. A model can also be the foundation for a framework that supports future direction, decision, and action.

Fortunately, past serendipity research has generated several process and conceptual models that we can adapt to construct our own framework for gainful serendipity.

Lawley and Tompkins[1], Makri and Blandford[2], Makri et al.[3], McCay-Peet[4], McCay-Peet and Toms[5], Rubin[6], and Sun[7] all have offered various models of the serendipity process.

All the models have their finer points, but they all have more similarities than significant differences. In general, a prepared mind applies insight to a chance or unexpected event, recognizes potential or makes some meaningful association, and follows through to a valuable outcome.

All the models are somewhat similar because, well, that’s serendipity in a nutshell. And my framework for gainful serendipity will be based on a very similar process model.

The value of a framework, after all, isn’t just that it makes it easier for us to understand the process, but that it makes it easier for us to operationalize the process in our lives.

A foundational framework for gainful serendipity can be based on the following basic formula:

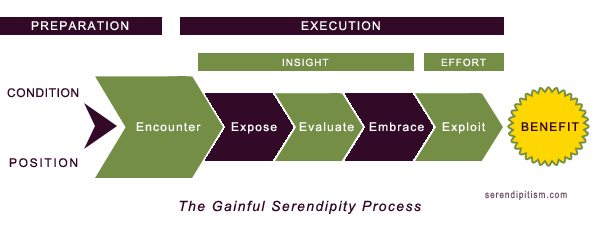

preparation + happenstance + insight + effort = benefit

We can then expand on this basic formula to produce a working conceptual framework for gainful serendipity:

This framework models the gainful serendipity process across two phases: preparation and execution.

Preparation

The preparation phase is where we ready ourselves for serendipity. This phase has two primary components: conditioning and positioning.

Conditioning

Conditioning is how we make ourselves cognitively and emotionally ready for serendipitous encounters. It is largely internal and intrapersonal, and encompasses such things as our acquired knowledge, learned behaviors, and informed choices.

The conditioning component consists of three primary elements:

- Properties. The personal attributes and characteristics that we develop. The qualities we cultivate to prepare ourselves, cognitively and emotionally, for serendipity.

- Principles. The set of guiding beliefs and propositions that we use as our philosophical and rational foundation. The ideas and concepts that help us choose our direction, make decisions, and act appropriately.

- Practices. The set of our behaviors and the specific actions we take to apply our properties and principles. How we operationalize serendipity in the real world.

Positioning

Positioning is how we engender or provoke serendipitous encounters. It is largely external and interpersonal, and encompasses such things as the actions we take, the interactions and relationships we initiate, and the places we go.

Like conditioning, the positioning component consists of three primary elements:

- Propinquity. Placing ourselves where we can make valuable connections. Aligning ourselves with like-minded people and positive influences.

- Promotion. Always taking outward action to advance our venture or goal. This doesn’t necessarily mean constantly evangelizing or “pitching.” Often, it’s just subtly making others aware of our cause.

- Proactivity. We must expect the unexpected and be prepared to respond appropriately when it happens. But we can’t just wait for opportunity and then adjust to the situation. We must take action to provoke the unexpected in furtherance of our goals.

Execution

The execution phase consists of the sequence of five primary steps that lead us from preparation through to benefit realization.

Encounter

The encounter is the unexpected or chance connection that we have been preparing and positioning ourselves for. This is not a conscious step that we take, but it is the first step nonetheless.

The encounter is the bridge between preparation and execution, and it is the catalyst for serendipity.

Exposure

Exposure is the step where opportunity is recognized, revealed, discovered, disclosed, or created. This is generally where the “eureka” or “a-ha” moment occurs.

Honing our opportunity recognition skill is an essential part of our preparation for gainful serendipity.

Evaluation

The evaluation step is where we assess the opportunity’s potential, both in general and as a fit for our own goals.

This step will often involve a good bit of nuts-and-bolts brainstorming and analysis.

Embrace

The embrace is where we willingly and enthusiastically accept the opportunity. Here, we go beyond simply realizing the opportunity’s value and start to clearly visualize where the opportunity can lead us.

This is where we experience the excitement of forecasting a new future for ourselves, and without the embrace, the opportunity is either rejected outright or shelved until it likely dies.

Exploitation

Exploitation is how we productively pursue the opportunity to benefit. This is when the rubber meets the road and the hard work begins. We applied our insight to the steps of exposure, evaluation, and embrace. Exploitation is where we apply effort.

Exploitation is really a step that leads us into a whole new phase that might involve starting and running a business, going to (or back to) school, writing our magnum opus, building a prototype, or any number of things that we might do to fully pursue the opportunity.

There is no specified sequence of actions to exploitation because every opportunity is different. However, because of our conditioning back in the preparation phase, we will know which direction to go when we get here.

Operationalizing the framework

It’s important to note that the process is not entirely linear or sequential. For example, we don’t simply abandon our properties, principles, and practices once a serendipitous encounter is made. We continue to use these throughout the process.

The process is also not necessarily discrete. Serendipitous encounters and benefits may be nested. After embracing a momentous opportunity and while exploiting it to the pursuit of our reward, we may very well experience related serendipitous encounters and benefits along the way.

The process may also be iterative, as we explore multiple possible paths to benefit. Or it may branch altogether, as opportunity evaluation could lead us ultimately down a more profitable path.

The framework provides a structure that can be universally applied, but still allows room for individuality and personalization. Everyone’s goals are different, so not everyone will place the same value on each property, principle, practice, or method of positioning.

The value of the framework is that it enables us to concretize serendipity, rather than thinking of it in vague or abstract terms. It allows us to conceptualize the serendipity process and provides us with direction and decision support. The framework also offers milestones for action and makes it easier for us to coordinate activities and communicate goals.

In his enlightening book, The Success Equation, Michael J. Mauboussin explains that in stable environments where luck is not a major factor, we can improve skill and develop true expertise through deliberate practice. Where luck does play a significant role, however, our best approach is to focus on the process we use.[8]

Basically, to improve skill, focus on practice. To improve luck, focus on process.

Gainful serendipity involves both skill and luck, to be sure. And there are some specific skills that we must develop and practice to prepare ourselves for serendipity.

But since chance plays such a pivotal role, we most effectively increase the likelihood for serendipity in our lives if we are guided by a clear process.